ME, BUT BETTER, my book about personality change, is out now. If you haven’t yet, please pick up your copy today. And if you’ve read the book, it would mean the world to me if you could leave an Amazon review. Thank you!

As I write in my book, many years ago, I was not very conscientious. Conscientiousness, or “grit,” is the personality trait that’s associated with being organized, timely, persistent, and motivated. It’s also associated with practically everything good, from living longer to earning more. But at that point in my life, I was bad at adulting, which means I was bad at conscientiousness.

Because I wasn’t in the habit of reading my mail, I nearly threw away the letter that offered me a full scholarship to college, and in grad school I regularly forgot appointments or ran late for interviews (for our silly little school-wide “news site,” but still.) I sometimes let people down because I just wasn’t organized enough to follow through on things. More humorously, I once gave my number to a cute guy, then forgot that I did that, then didn’t respond when he texted me because I thought he was a scammer. (He won me over with “I’m confused why you’re ignoring me because you asked me to text you.” Swoon.)

But as I also write in the book, not long after that period in my life, I changed. I became way more conscientious, through a process of maturing, goal-setting, and frankly, getting better at driving. But one other thing contributed to my increase in conscientiousness: I got my first iPhone.

Suddenly, instead of printing out Mapquest directions that I struggled to read as I sat in traffic on the Santa Monica freeway, I had Google maps talk me through the directions in real time. I had a constantly-updated to-do list in my pocket, and calendar reminders that popped up throughout the day. I could read and write emails on the go, which meant I could let people know if I was running late or had to change my plans.

Years later, my phone has continued to be a conscientiousness tool. Sure, I still waste time on social media, but overwhelmingly, my phone mostly helps me stay on task. If I don’t have my phone, I literally can’t do anything that day because I don’t know what I’m supposed to be doing.

The fact that the iPhone helped me, and likely lots of other people, become more conscientious sits somewhat awkwardly with a recent Financial Times article that purported that people are becoming less conscientious, and that placed the blame in part on smartphones. “The advent of ubiquitous and hyper-engaging digital media has led to an explosion in distraction, as well as making it easier than ever to either not make plans in the first place or to abandon them,” writes author John Burn-Murdoch. (I wrote about Burn-Murdoch’s analysis here.)

So here we have evidence that people are becoming less organized, because of the very thing designed to help people stay organized. To get to the bottom of what’s really happening with conscientiousness, I recently spoke with Brent Roberts, a personality psychologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign who has studied conscientiousness extensively. Our full conversation is available on the latest episode of my podcast, Why We’re Like This, and some snippets are below.

Olga: What is conscientiousness?

Brent: Most people would understand it under the term “grit,” which is a more popular, shorter, and much more effective marketing of the idea. It’s your willingness to work hard and to persist in the face of often setbacks and the like.

That’s one aspect of conscientiousness. Other aspects are whether you keep your desk neat and clean and things tidy around your house. That’s the organization facet. There’s also your ability to inhibit your impulses. So if you really can’t stop eating the cake or something like that, that’s what we think of as impulsiveness, which is the opposite of conscientiousness. There’s responsibility, which is your propensity to follow through with promises to remember those birthdays, to do good things for other people on a schedule.

There’s also kind of a conventional aspect to it, like following rules. So people who really like to follow the rules and will be aware of them, those folks are also higher on conscientiousness. Young people usually don’t [want to be conscientious], but as you get older, you usually do.

Olga: So why is conscientiousness associated with seemingly everything good, like living longer and making more money?

Brent: When you’re a kid, kids who are more conscientious do better in school. So they’re studying, they’re working harder in classes, they’re getting better grades, then they’re getting asked to go to a higher education and they’re finishing their college degrees. It plays out in work where people who are more conscientious tend to be seen by their supervisors as better employees. So they actually perform better on the job. It’s not only work, but it’s also love. People who are more conscientious tend to have more stable, long-lasting marital relationships or just stable relationships.

Then it predicts health. People who are more conscientious … they don’t drink as much, they don’t do as many drugs, they exercise a little more. They tend to listen to what people say about what should be eaten. And so they tend to have better physical health. And then that results in a not-so-confusing relationship with longevity.

And then, of course, because they tend to do things that are rewarded by lots of things in society, either your bosses or partners, they tend to experience better life satisfaction. That combination is pretty profound: avoid problems and get goodies from the world. Money doesn’t buy you happiness, but it does keep a whole heap of trouble off the front porch, as they say in Oklahoma.

Can people increase their conscientiousness and if so, how?

If you believe our studies, yes … Set your goals better, organize your goals better, give yourself some accountability systems so that when you actually achieve things, you celebrate and you actually track what you do. For those of us who are not conscious, though, there’s a follow-through problem.

I have benefited greatly from some of the skills that consultants teach in terms of, like, organizing your to-do list. For years, I did a completely ridiculously stupid to-do list, which was not a to-do list. It was a project list. Which was of course a psychological burden because you never get your projects finished. So every day I’d open up my to-do list and it would remind me of how inadequate I was. I get depressed, close it, try to ignore it. And you know, I went through some of the books. “Oh, so you should do a to-do list each day on things that you’re going to get done that day.” I thought this was amazing until I turned to my wife and asked her about it and she’d been doing it for decades.

And the other idea is getting things out of your head. Not using your own brain to organize all your information. It’s really good to park your brain someplace else … it’s another little technique that works really to make you look a lot more responsible than you really are.

Is conscientiousness declining, as this FT story suggests?

You see it in some cases, sure. Did it happen in the Understanding America study [that the FT used]? Yes. I would not say that the data was wrong or that it doesn’t exist.

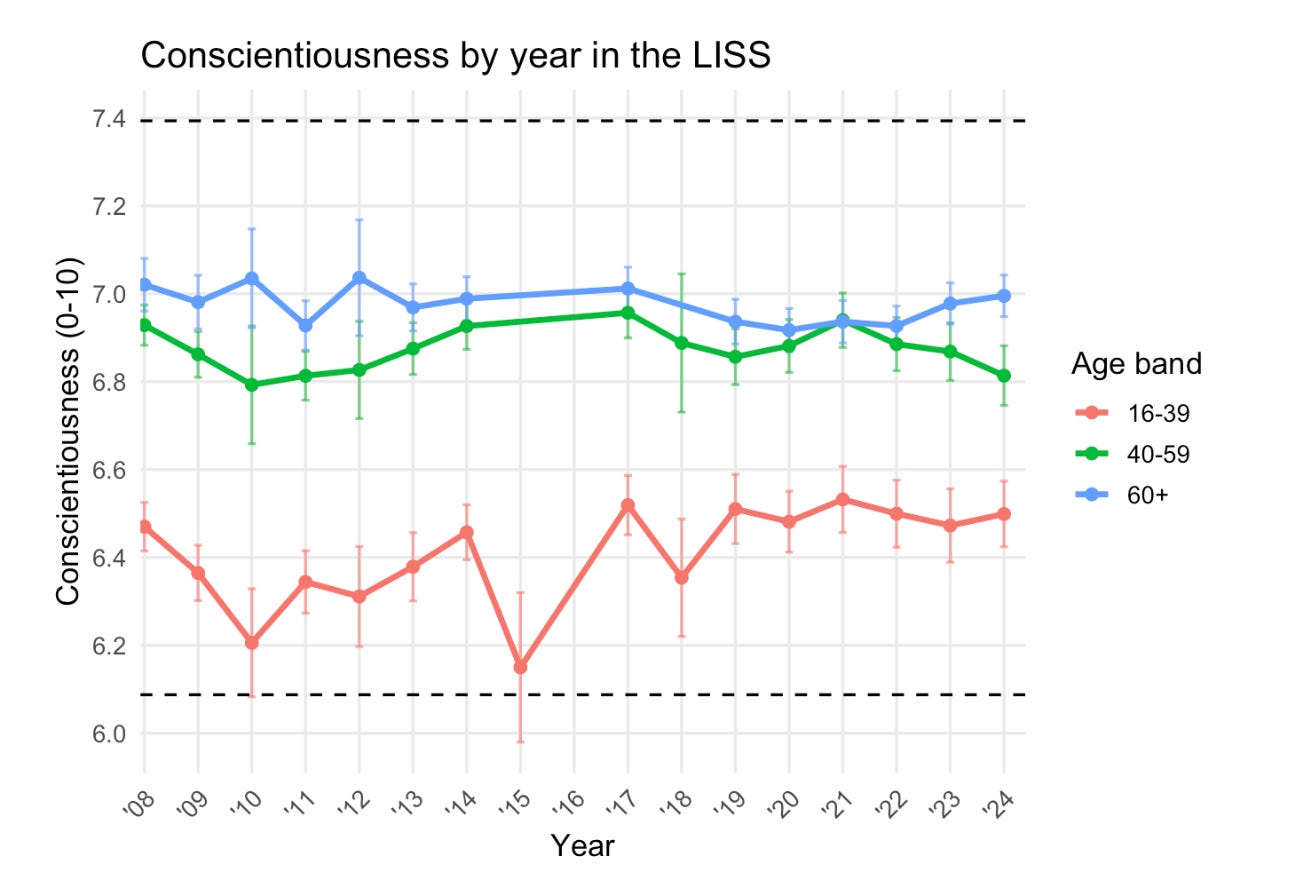

The question to ask is, does the effect replicate in other data sets? So there’s this study of the same period that asked a bunch of Dutch people their responses to the yes-no questions on personality inventories. And that sample, starting in 2014, people increased in conscientiousness. And it didn’t actually decrease at all until just recently.

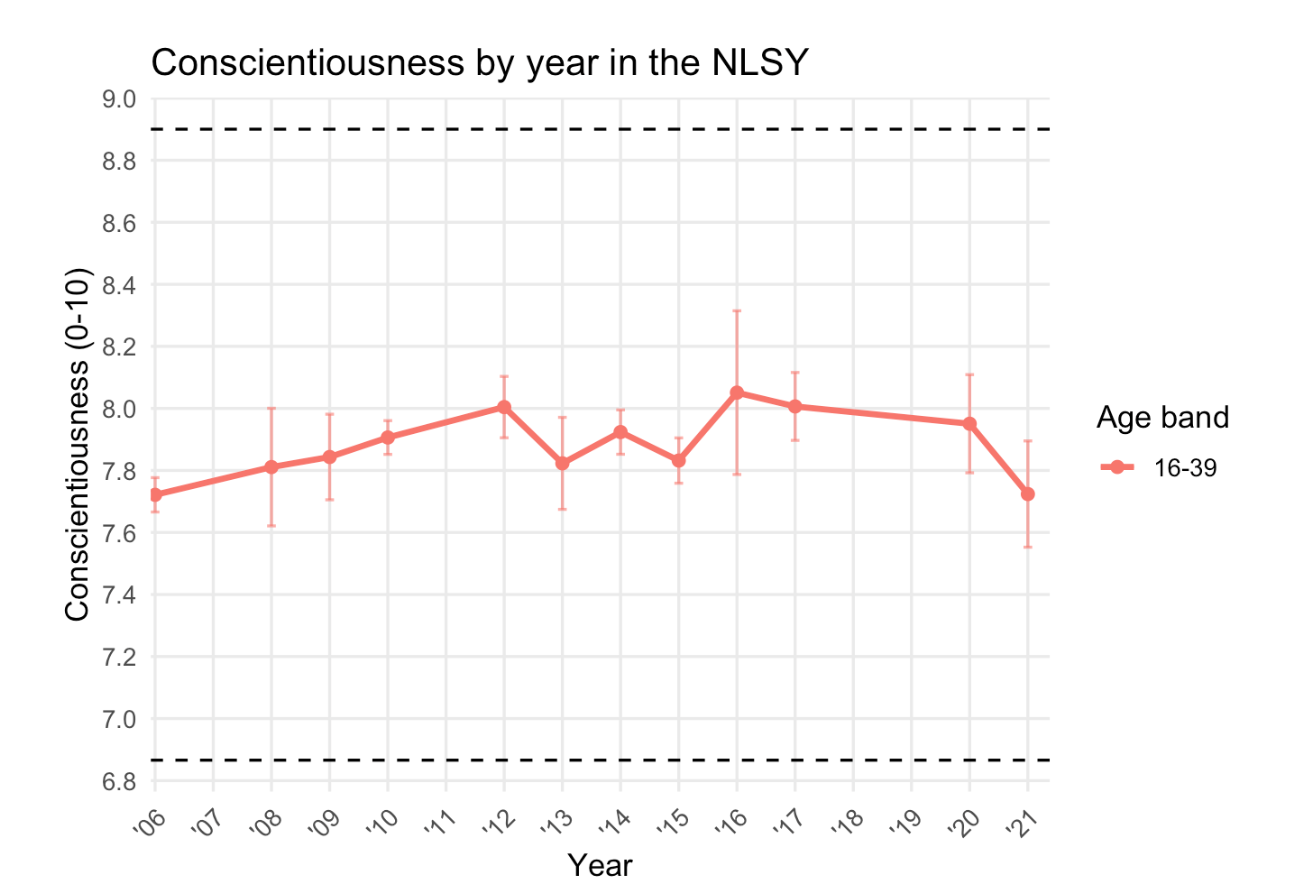

There’s another study called the NLSY, the National Longitudinal Study of Youth, that also tracked conscientiousness during the period.

Lo and behold, did those people go down? No, they kind of went up a little bit, went down a little bit, mostly were flat.

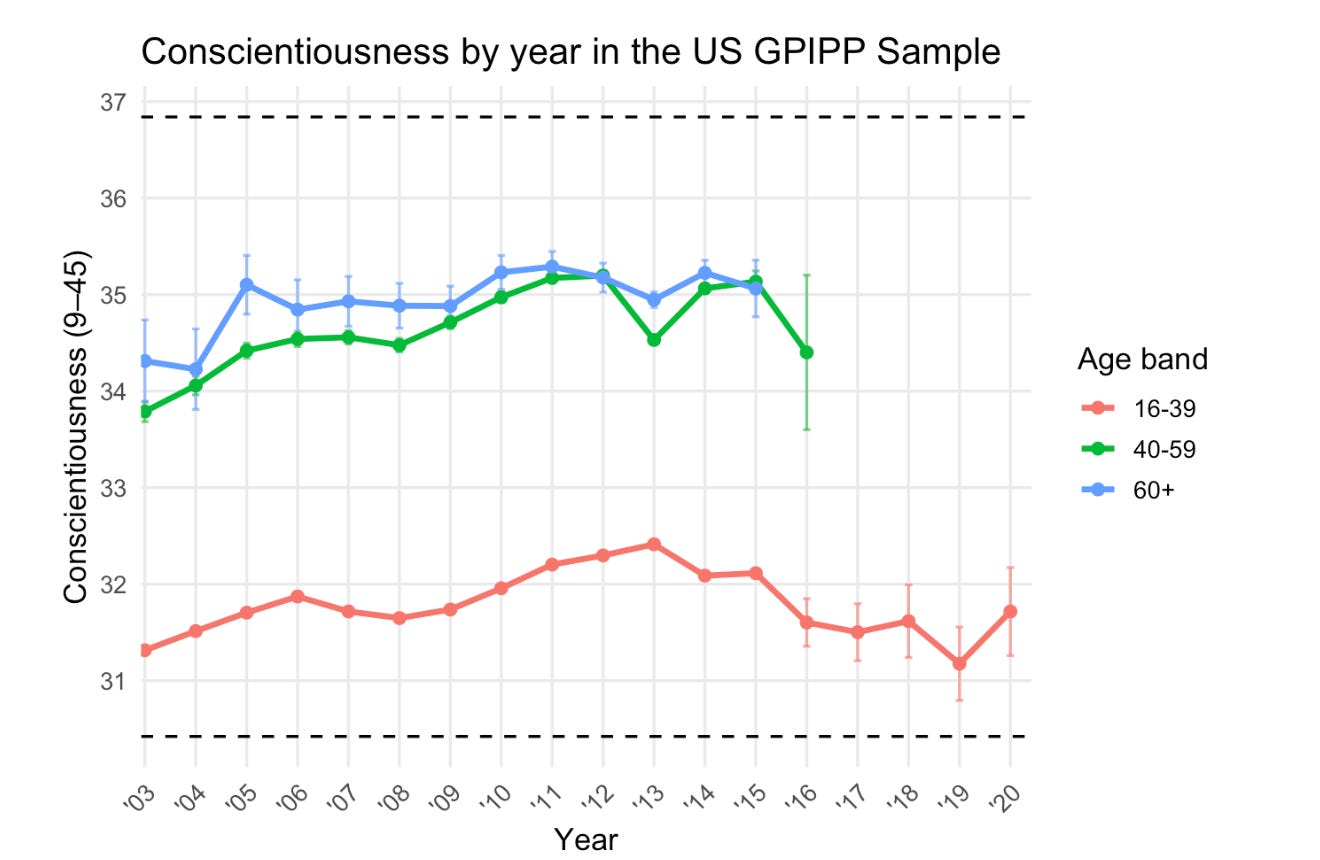

In our data where we track people over a longer period of time, do people start going down in 2014 or so? A little bit, just much smaller. But what was really cool is we have history in that data all the way back to 2000. And you see that actually, people were increasing [on conscientiousness] and that the peak year for people was 2014.

So if you bother to look at other data sets, you don’t see the same pattern. And in the aggregate, there’s nothing so dramatic as to lead you to conclude that people have fallen off a cliff when it comes to conscientiousness.

At this point, given what I’ve seen in data, and it’s across lots of longitudinal studies, at least a dozen, there is no general decline. There is no freefall on consciousness in young people.

Are smartphones affecting conscientiousness?

I mean, don’t want to say cell phones or smartphones don’t have any effect on people. I actually do think they have an effect, but it’s not using smartphones. It’s the damn programs that you use on them that make you feel bad. [Smartphones are] a human nature accelerant. It can do lots of things, but mostly it makes things bigger.

If you take these other samples that had the same young people over the same period of history and you do not see a decrease, it’s it’s a really good counterfactual and it really says, you should not conclude that the easy answer, which is smartphones, is the right answer.

I saw it with my kids where, we had a particular setup where they were in school districts that separated them so they didn’t see each other after school or go to their neighbor’s school. Then they got on social media in some sense, usually Minecraft, and then played each other all afternoon with a group of kids who would have never been interacting. They also had bad experiences with people on that platform, but I also saw them interacting verbally so much more than [I did as a kid.]

Now they text each other. And then they would have a discourse that would be, from my perspective, rich in terms of the social exchange and emotions. They got really good at saying, “hey, you hurt my feelings” and “oh, I’m sorry.” And the sophistication of the social interaction was far beyond a 12-year-old or 14-year-old or something like that. And it was just simply because the base rate of interaction was so much greater.

It’s humans, man. We’re just using a vehicle. So I think the idea to paint all the problems of society into that little box is looking askance to the real problem, which is us.