When the Snake Oil Works

There's no scientific basis for acupuncture. So why did it work on me?

As I’ve written previously, I’m an insomniac. I wake up in the middle of the night, almost every night, unless of course nothing new is going on in my life, and Trump is not the president, and my husband has not done anything dumb lately, and it’s not below 60 degrees outside, and the mortgage interest rate is not over 5 percent, and the latest jobs report is strong, and none of my friends could potentially be mad at me. All of these factors have literally never aligned, so suffice it to say I’m often awake in the middle of the night.

My insomnia is related to my high levels of neuroticism, the personality trait that’s associated with depression and anxiety. Neurotics have a high degree of “pre-sleep arousal,” which is unfortunately not as sexy as it sounds. It means that before we go to bed, we inflate a big party balloon of all of our worries. At some point in the night, it pops.

Usually, I wake up to my heart racing, and it takes a while to slow. You’re not supposed to look at your phone, but I do anyway. You’re not supposed to worry about how tired you’ll be the next day, but I do anyway. Usually, I’ll toss and turn for a few hours, trying to solve my latest existential problem through the fog of my 3 a.m. mind. I’ll google things. I’ll write mean emails I don’t send. I’ll write reminders to myself that I only half understand later. The next morning, I am inevitably so. incredibly. tired.

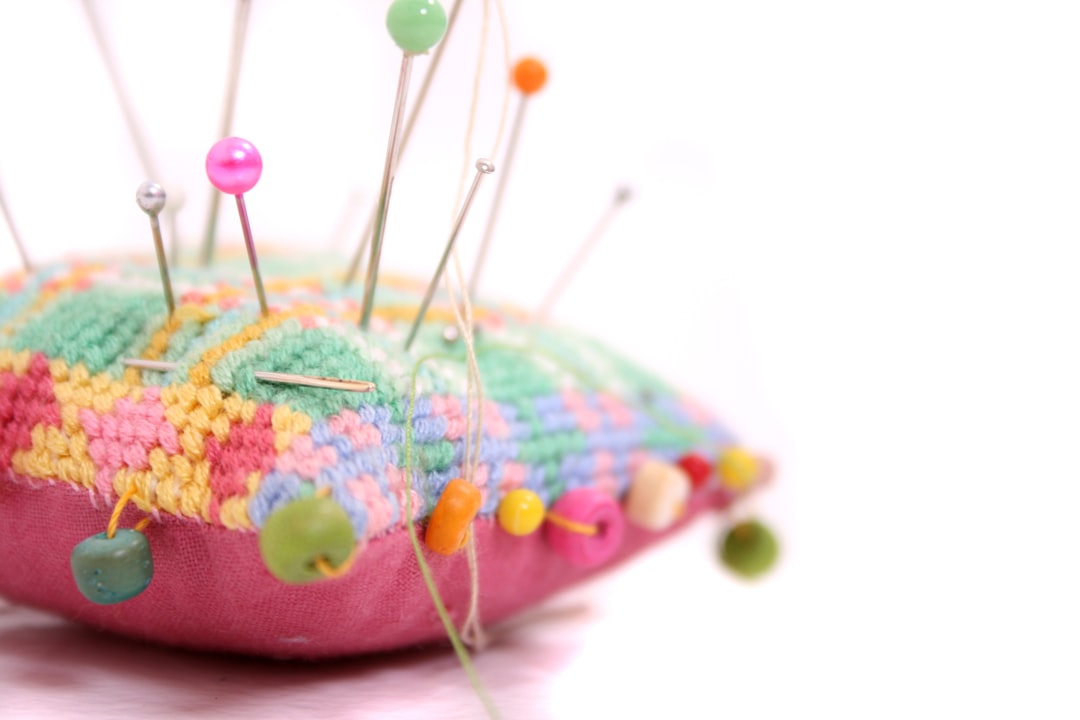

At the suggestion of some of my Twitter interlocutors, a few months ago I decided to seek relief in acupuncture, the alternative-medicine practice in which small pins are inserted into the skin and left there for about half an hour.

Because nothing seemed to be working, I was willing to give it a shot. But I was doubtful it would do anything. I get that acupuncture has helped a lot of people, and that many swear by it, but I find it dubious. The stated “science” behind acupuncture is that the body is full of energy called “qi” that can be moved around through needles placed along its “meridians.” This strains credulity for a lot of people, and it does for me, too. If you so much as mention acupuncture to science-scold types, the kind who scour the internet for overstated p values, you’ll be met with derision.

Western scientists I talked to aren’t completely sure how acupuncture is supposed to work, or if it does. Some researchers think the insertion of the pins might release endorphins, our natural painkilling neurotransmitters. Or it might turn down the brain’s perception of uncomfortable sensations like pain. Or it might somehow tweak the connective tissue, affect blood flow, or just serve as a convincing placebo, making the patient feel cared for and, therefore, more relaxed and pain-free.

The scientific literature regarding acupuncture’s effects on sleep is even more sparse, but some researchers think the practice might help soothe the sympathetic “fight or flight” nervous system, or stimulate the mysterious and all-important vagus nerve, which connects the brain to the gut. When I asked the sleep experts, their advice was, basically: They’re not sure acupuncture does work, or how it works. But if it helps me sleep, go with God.

I was desperate, so I reluctantly signed the forms at the acupuncturist’s basement office, including an arbitration agreement in case “something goes wrong.” The acupuncturist sat me down and asked me what my issue is—it’s that I startle awake at 3 a.m. every night.

He said he suspects that the problem is my liver, since that’s “the time of the liver.” He took my pulse by pressing down on my wrists with his fingers. “Your liver pulse is weak,” he said.

He took a picture of my tongue, whose veins and patches confirmed the liver issue, he said.

“Not the right shape,” he pronounced it. “Too narrow.”

“Not sure there’s anything I can do about that,” I said.

Though I found the tongue examination questionable, Helene Langevin, the director of the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health at the NIH, told me the tongue is more important than it might seem. “I think that this is information that in Western medicine, we should be paying a lot more attention to,” she said. “If you think about it, your tongue is connected to your digestive system. It’s kind of a window into the inside of your body.”

Regardless, the acupuncturist concluded that my issues were bound up in the liver. In fact, a lot of society’s issues were, too. He said crime goes up in the fall, which is the time of year associated with the liver. Apparently peoples’ livers get so out of whack, it leads them to violence. Maybe we should defund the police and fund hepatologists.

“Doesn’t crime go up in the summer?” I said.

“The fall,” he insisted. (It’s the summer.)

None of this was boosting my confidence in the evidence behind acupuncture. But I was already there, and, frankly, I was kind of curious where this would go.

The acupuncturist led me into an austere back room adorned with a poster depicting all the body’s “acupoints,” and onto an exam table. He stuck tiny pins in my head, hands, legs, and feet. The pain was on par with an ant bite, and only lasted a second, but also like an ant bite, each prick itched slightly. For 30 minutes, I lay there looking like Pinhead, figuring soon I would at least be done with this exercise. I tried to meditate, then gave up and made a to-do list, then shifted to obsessing about whether the needles were truly sanitized. (They were.) Then I paid $125 and left.

Afterward, I had my first night of uninterrupted sleep in weeks.

I was, to put it mildly, a little floored by this result. How could something I don’t believe in at all, even as it was happening, have relaxed me so profoundly?

A few theories on why this might be:

The placebo effect worked on me, even though I didn’t “believe” in the placebo. A few studies have found that so-called “honest” placebos—in which the person knows they’re getting a sugar pill—still work. These “open-label” placebos have been found improve symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. They ease chronic pain, compared to a control group. A fake pill alleviated feelings of guilt, even when study subjects knew there was nothing in it. Even when you know the treatment is a sham, “the brain can fill in the picture and improve symptoms,” as NPR put it in 2016. I might have known that the evidence for acupuncture’s effect on sleep was spotty, but just doing something to help my sleep might have been enough.

Acupuncture works! If you are a science writer long enough, or hang around them long enough, eventually you’ll hear the phrase “absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence.” That is, just because we don’t have the data to show something is true, doesn’t mean it’s not necessarily true. The studies showing positive effects of acupuncture on insomnia tend to be sketchy, but who’s to say there’s not some thousand-patient randomized controlled trial waiting in the wings, ready to prove me wrong. It could be that this is actually a very good insomnia treatment, and Westerners are sleeping on it (no pun intended) because alternative medicine is not taken very seriously here. That would still leave quite a bit of ‘splainin to do on the mechanism of action, but I’m open to this possibility.

Rituals are powerful. Finally, there could be something else going on here that is more mysterious, and isn’t limited just to acupuncture. Acupuncture is a type of ritual, and it’s possible this ritual itself had a calming effect. It might have placed constraints on the dizzying freedom of anxiety.

I had always thought rituals were silly and unscientific, but there is, in fact, evidence that routines can reduce anxiety. People all over the world use rituals to help them manage their stress, writes the anthropologist Dimitris Xygalatas in his recent book, Ritual. In studies, women in war zones who recited psalms had lower stress levels, and study participants who performed a fake, spell-like ritual were better able to manage their anxiety on math tests and other stressful tasks.

In fact, I’ve been participating in an anxiety-reduction ritual my entire adult life. At least once a week, I do yoga, which involves performing a series of well-known postures, or asanas, often in a slow, repetitive way. Even in its hyper-Americanized form, I enjoy the predictability of yoga’s rhythms. Yoga offers evidence that even I can chill out: When I started out, I hated the savasana resting pose at the end of class, but now, I relish it.

Anxious people loathe uncertainty, so in uncertain moments, we try to find control in other domains, like by wearing lucky socks, saying a prayer, or, in my case, doing a vinyasana. “Rituals,” Xygalatas writes, “serve as an anchor in the storm that is our world.”

Of course, ball players often strike out while wearing their lucky socks, and prayers for rain don’t always bring any. I often walk out of yoga class and right back into a work disaster. The fact that the ritual won’t meaningfully change the situation doesn’t seem to matter; it’s the illusion of control that soothes. It’s no accident that we see rituals pop up in high-stakes, uncertain situations like professional sports, casino floors, and exam rooms. During the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, Google searches for prayer skyrocketed. “By April 1, 2020, more than half of the world population had prayed to end the coronavirus,” writes one economist who crunched the data. Like all rituals, the praying helped—if not in delivering a certain outcome, then at least in reassuring an uncertain world. Maybe that’s why acupuncture helped, too.

The takeaway here is not that everyone should try acupuncture. It’s not even that everyone with sleep problems should try acupuncture, or any other new-agey treatment. I went back to the acupuncturist a few more times, but it never quite worked like that first session. Soon I was back to tossing and turning.

But when you’re desperate, it’s worth considering whether you’re writing off something that could potentially be beneficial. There’s so much of human health and psychology that scientists just aren’t sure about. Meditation, yoga, prayer, SSRIs, exercise: No one totally knows why these things alleviate various problems, just that they do. As long as the treatment is non-addictive and generally non-harmful, and it’s not displacing a more evidence-backed medical treatment, and you’re dealing with a problem that itself is kind of mysterious and fuzzy, it sometimes literally can’t hurt to try. Hell, it might actually help.

your overall tone sounds very condescending

The one-time effect on your sleep is a lot less mysterious than if had worked more permanently. As a golfer, let me draw your attention to the hole-in-one phenomenon.

This can happen to Joe Schmendrick once.

More than once and you're either Tiger Woods or lying. And even Tiger has not had that many.